In a bouncinette. My feet splashing in a bowl of water. Golden light sneaking through the leaves warming patches of my legs. No top. Or perhaps a cotton singlet. Under a hibiscus tree. Festooned with flowers the color of musk sticks. Nappy. Bottle. I must have been about a year old. I smelt BBQ.

The lush and exotic blooms stood out as large unapologetic blurters, show offs, in monochrome suburban Preston in 1969. In gardens that considered lavender, geranium and daisies ‘rather loud’, agapanthus as a ‘pest’ and hydrangeas, the color and shape of the hair of the nana’s that sat in the pews in front of me at church, as beautiful. And kind of mystical. ‘You know the color of the flower changes depending on the soil.’

I wondered whether I would worship these dumpy, ungainly flowers when I was an old lady.

I was about four years old and Mum asked me what my favorite flower was. ‘Forget-me-nots’ I replied. ‘They’re not a flower, they’re a weed.’ ‘Says who?’ I said.

The smell of stew, the sound of ‘Matlock’ and the weight of my parent’s emotions leaking into me was pierced by that moment. Those big happy flowers like you saw on Hawaiian shirts. The ones people wore on holidays. Whatever they were.

“Why do American’s speak in such loud voices? So you can hear them over their loud clothes.”

My parents weren’t big on the outdoors. Outside was something you tolerated going from one inside to another inside. They didn’t own runners or bikes and I never saw them swim. Raised Catholics and therefore to think of their body as enemy number one was probably what led to my father poisoning his with smoking and alcohol which resulted in Mum obese with shame and comfort food. The demonizing of desire may have been the reason they shut themselves down physically from the elements. The weather on their skins may have aroused their bodies so much their bodies would wake and mourn of neglect. So they stayed inside. In their insides.

At four I remember running naked through the bush at Wilson’s Prom with my cousin Kate-Louise who was only three months younger than I. The bush was all McCubbin. Kate-Louise explained ‘Nude is not wearing clothes. Rude is not wearing clothes and showing off at the same time’. I must have been concerned because I remember being relieved by that explanation. Kate-Louise committed suicide on my 25th birthday. I was living in Tokyo. It was my Mum who told me ‘She threw herself under a train.’ She was 24.

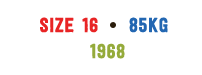

It was the summer before I began primary school and we went on that holiday. Our very first of only a handful of holidays. I was 4, David, 3 and Elizabeth, 6. We loaded up the Valiant and my grandparent’s white canvas tent and took the four-hour drive down to Wilson’s Prom.

Mum’s family had camped in Wilson’s Prom when she was a teenager. Back then hardly anyone knew it was there. I have no idea how they even knew about it.

Mum told me she would set off with a book and a can of pineapple juice in the morning and come home late afternoon. She would find a shady spot, put the can of pineapple juice in some cool shallow water and spend all day reading, swimming and writing letters to my father.

This always seemed strange to me. I could only ever remember Mum barely tolerating Dad and never remember her reading a book, let alone writing a letter. Least of all to Dad.

The breathtaking slap in the face of the view of glittering Norman Bay and the magical winding Tidal River with its secret rock caves and silvery schools of fish made me blink my eyes to make sure I wasn’t dreaming. Squeaky Beach. The sand really did squeak when you walked. It was magic. The stretch of my pink paisley bathers we’d bought from Venture and the joy of my red bucket and spade. The savory canned smell of Tom Piper Braised Steak And Onions. The feeling of a lilo under a sleeping bag, under sand, under my sunburn. It was intoxicating. The brightness of the parrots, the chat and laughter of the other campers, the sting of the March Flies with their rainbow sheen, and that moment waking up remembering you were on holiday. Camping. And outside the flap of the tent were adventures waiting.

We were dirty, grubby, hungry, wet, warm, scorched, parched and outside. And I felt a happiness I have been drawn to ever since. A happiness of being exposed.

Leaving Tidal River I was heartbroken. I thought we had moved there forever. It was grey, cold and raining. I was wearing shorts, a jumper and thongs. My legs were freezing but my back radiated from sunburn. I was holding a bucket of starfish and did not understand why I couldn’t bring them home.

“Because they will die,” said Mum. “They live here. They’ll die at home.”

Outdoors I remember first feeling everything.