Another brilliant piece from a GUNNAS WRITING MASTERCLASS writer.

I’m sitting on a beach and the sun is on the edge of coming up. It’s that time when you can’t work out if the sky is black or the darkest shade of indigo. The light shifts; the cold is coming down; like a reverse dew point.

Why is it always cold before dawn? What shifts? Is the earth like me? Does she want to stay snug under the downy blankets of the soft night; warm and silent and dreaming of unexplored reality?

I watch the stars and search and search for the Pleiades. They are the seven sisters of many cultures. As I sit on Kulin lands, the sisters are Wurundjeri. They were seven sisters who had the gift of fire and were ticked by Waarn the crow into giving him the fire. They were then taken up into the sky where their glowing fire sticks became the Pleiades*. Are they happy in their new home? I wonder what they are trying to say to me. If only I could hear them speak.

The waves lap gently on the beach. The tide is out and there is little wind. It’s that stillness that comes with the cold before dawn.

The birds begin to stir and tweet as the deep indigo sky starts to imperceptibly lighten and the middle world of consciousness moves to return to the awakened states of dreaming. But all is yet still. It is a liminal time – not one thing nor the other.

I recall being nineteen and looking out a bedroom window in Parkville at 4am. It was a cold August night and the streetlights pooled below the sodium lamps; the light split and shattered by the ice crystals in the fog. I felt suspended in an alternative reality which I never wanted to leave. Where time stood still and I could be anything I wanted. And I wanted.

Yet I was suffocating in a noxious cloud of existential sadness believing that I was trapped by a future that I couldn’t grasp. Time proved me correct. I was too young to understand the need to fashion my being in the image of what I chose to be.

But enough of that.

I am watching the lights of the container ships cutting up the south channel. I contemplate where they have come from: Shanghi, Singapore, Shenzhen, Rotterdam, Bremen … the list is endless. I see industrialised ports working 24/7 in a haze of artificial light with noise and ceaseless activity. Straddle cranes, trucks, officious customs officers and the luminescent energy of wharfies who went home from work in a pine coffin.

It’s more romantic when you don’t think of that. I will instead contemplate George Johnston writing about the liners coming up the Bay in the 1930s. They emerged out of the sea fog, bringing a hazy ephemeral umbilical cord from ‘home’.

I am so distracted from my thoughts about the earth and the lightening indigo sky that I continually throw myself out of the liminality that I crave. The lost liners of the 1930s in their pre-war deco glory speak to me of the broken lines in communication and the small cracks in relationships that grow into chasms that can never be bridged.

These liners, long gone by torpedo or the blowtorch of ship breakers, evoke the musty smells of the slow decay of old Europe; much like the moldering pool at Ripponlea. The change rooms smell of the rot of the old – like they will never be quite clean. The creepers grow though the cracks in the windows and thrive in the humid half-light.

Europe. This is where my ancestors came from. I don’t think they considered the decay. They just wanted a new life somewhere else. They landed not far from where I am sitting in the dense cold of the morning. The coastal salt scrub of Point Ormond would have seemed exotic and dangerous. I feel safe and encompassed by the scrub surrounding me.

It’s 5am and I realise that I don’t know them. Yes – an absurd realisation as they were long dead when I took my first breath. Yet I don’t know them in their Englishness and their transplantation of ‘home’, half way around the world. Would they recognise me as one of them? I doubt it but that doesn’t worry me.

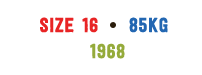

I am displaced from those who bore me, whose genes I keep alive. I am sitting on Country that they wouldn’t recognise in a time and place that would make no sense to them. I am not them. Who am I in relation to my ancestry and to time as I walk as if a blind woman through my days?

The sun is starting to spill from the east and the stars have all but retreated. The ghostly liners have vanished and I start to hear the garbos and the street cleaners on their morning rounds.

If I ignore the sounds of the city awakening, I hear the wind as it picks up, kicking off the water. I hear something but like the song of the Pleiades, I can’t quite understand what it is whispering. The saltbush rustles and the paperbarks creak in the cool breeze as the earth begins to awaken from her slumber.

And that is what they say. “Awaken from your slumber. Don’t try to hear my voice but listen to my thoughts in your heart. We were here before time and we will be long here after you are forgotten. Don’t sit staring into middle distance and parley with me for time; that will only see you safely to oblivion. You have what you need.”

“Listen to the call of the Pleiades, dance and sing and write and riot and don’t take refuge in that old room at 4am. Don’t take refuge in anything. Burn up in the brilliance of existence.”

So, on the beach as the sun is flooding the new day, I must hasten to attend to my dreams, listen to the wind and the waves and the sea as it crashes on the breakwater and the sun and the moon and frolic amongst the stars. But I will always come back to sit in the liminal time where nothing is quite as it seems and the sky is moving from velvet black to indigo satin.

* Mudrooroo (1994). Aboriginal mythology: An A-Z spanning the history of the Australian Aboriginal people from the earliest legends to the present day, London, Thorsons, 35–36, ISBN 978-1-85538-306-7.