Another brilliant piece from a GUNNAS WRITING MASTERCLASS WRITER.

Tony watched his father stroll across the schoolyard when he should have been focusing on his maths equations. He was staring out the window because it was maths that he was meant to be doing, and he hated maths. He hated numbers. He hated that there was always some trick he was meant to know, a trick that made sense to everyone else, a trick that made it easier for everyone else, except for him. So because it was maths and it was hot, and he never really needed much of an excuse to get lost in his own thoughts whilst doing maths, he found himself staring out the window. And noticed his father.

His father looked happy enough strolling along. Strolling? No. Striding. His tall figure was moving purposely across the searing asphalt. Tony knew it was unusual for his father to be walking around in the middle of the day, yet he hadn’t seen him for a few weeks. Why would he be walking through the school? It was a bit of a thoroughfare for the locals on their way to the strip of shops.

Why wasn’t he at work though?

All Tony knew was that he worked for the ‘Tramways’. He wasn’t a tram driver, he wasn’t a conductor but that’s where he worked.

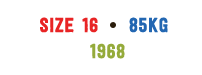

An 8 year old can make sense of even the strangest situations and he returned his dad’s wave with a cautious flick of his hand, and that was acknowledgement enough for his father to continue on his journey through the school grounds. Tony knew his mother would be working at her Aunt’s deli and his father was heading that way.

That was all the thought he gave to an unpleasant scenario whereby his feuding, and now ‘estranged’ parents would have some kind of ugly interaction.

Tony turned back to his maths book and concentrated on the task at hand. Should that 1 be carried? Where did it go though? He popped it down in the middle, immediately questioning its position. What was the 1 even worth? Why was it just 1? He was positive he’d counted past ten. Maybe it was ten? Should he have written a ten then? It was all too confusing. He wondered whether he’d been ill the day they were taught why it was just a 1 that got carried over, and to where. He had been sick a lot.

Tony had suffered from asthma from a baby. His mother told many stories of him turning blue and her fear she’d lose him, wheezing in her arms. He couldn’t recall the last time he missed school due to an attack though, so it must have improved.

‘Emotional Asthma’ was his grandmother Ussy’s diagnosis.

Tony now lived with Ussy. Her name wasn’t actually Ussy. It was Alice. She would refer to herself as ‘Us’ when he was a very young child, “Come inside with Us”, “Have something to eat with Us” that he had thought that her name was Us, and because he was very young he called her Ussy. It stuck.

She was Grandma to his much older brothers. She wouldn’t have accepted any nicknames from them. She didn’t care for them. Nor did she care for their wives. Tony was her firm favourite.

Tony was his mother’s favourite too, something he’d known all his life. In eight years time, when doing Matriculation he would reluctantly read D.H Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, and become uncomfortably aware that he and his mother were similar to Paul and Gertrude. It was the only thing that he would connect with in the story, and thankfully allow him to compose a half-decent response.

He hadn’t turned blue with asthma for a while. And he quite liked the new living arrangements with his mum, Ussy and Grandpa in the cozy two bedroom fibro. Their old house, the one he had lived in as a family may have been bigger but it wasn’t a house Tony remembered with any fondness.

When was the last time he’d spoken to his father? He gave it only the briefest consideration as he glanced out the window, confident the “one” was in fact, “ten” so it needed to go in that area…column? Was it a column? He should know that, but he was on a roll to complete his equations so returned his attention to getting them done.

Tony scanned the street for the imposing figure but he’d vanished.

His thoughts were interrupted by his teacher, suddenly demonstrating something on the blackboard. He watched as Mr. Wilson explained the process once again and was relieved that he wasn’t the only one who had initially been confused. Mr. Wilson was good like that. He never made anyone embarrassed when they got something wrong, and tried to make sure everyone understood, explaining things in a different way if that’s what they needed. He was the youngest teacher he’d ever had and the only male teacher he had known. Tony suspected he was around the same age as his brothers.

Energised with a renewed conviction Tony went over his first answers, corrected a couple then returned to working on the rest. Perhaps maths wasn’t so bad after all. It was making more sense to him now.

“Hey, Keogh. There’s your dad.” Charlie Murphy motioned to the playground and Tony once again watched his father re-cross the asphalt, this time with even more assurance in each long stride.

Tony waved and his father grinned broadly, waving back rather enthusiastically. Tony was uneasy. His father wasn’t the grinning kind. This public demonstration of delight encouraged Tony to watch him leave the school grounds with great suspicion. He returned to the maths and tried to put his father’s strange behaviour out of his mind.

After lunch the Headmaster appeared at the door and beckoned Mr. Wilson out into the corridor. They spoke in hushed tones before Mr. Wilson returned and quietly asked the students to continue with something they’d begun in the morning. Tony had observed the situation with the interest an eight year old would usually take, that being not much.

“Keogh.” Mr. Wilson announced as the bell rang and students began to dart out of the classroom. “Anthony Keogh, bring your maths to me please?”

Tony groaned internally, yet obediently took his maths book up to his teacher’s desk. Charlie Murphy laughed.

“I just want to go over some of your sums with you so I know you completely understand, Anthony.”

They sat there and completed sums together in the furnace of a classroom until the Headmaster appeared and gave a reassuring little nod.

“Goodo, Keogh.” Mr. Wilson sighed, “Off you go then, and go straight home,” he paused, “not to the deli.”

Tony thought he glimpsed pity in the young teacher’s eyes.

“Yes, sir.”