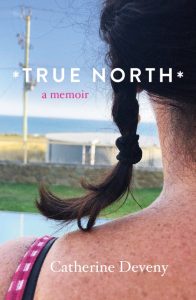

An edited version of the final chapter of my memoir True North published by Black Inc Books in 2022

Death is the sound of distant thunder at a picnic.

Death is the sound of distant thunder at a picnic.

W.H. Auden

On a very ordinary but beautiful Saturday in May, a little shy of eleven years after those grapevines were replanted in their fertile new ground, we were told Mum had two weeks to live. She’d been very sick for a while, in and out of hospital, and was transferred from a ward to palliative care the same evening she received her terminal cancer prognosis. She died two weeks later. Timing on point.

* * *

I was relieved to hear Mum was dying, but not convinced. I said to my mate Lou, ‘Two weeks? Don’t bet on it. It could go on for years. They live forever these days; medicine is too good.’

My fear was not Mum dying. My fear was that Mum wouldn’t die.

She lived alone and was deteriorating more and more as each year passed. I couldn’t bear the thought of her dying alone in her unit, having to care for her in my home or, worse still, her dementing and desiccating in an aged-care facility for years. Her life had been tough enough. My hope was that she’d die in a safe place, in no pain, with her marbles intact and still with her driver’s licence. As her mobility became more and more compromised, I feared that having her driver’s licence cancelled would be an even bigger blow than being moved into a home. She loved the independence of driving.

Palliative care was an incredibly healing place for all of us. The shift from finding out what was wrong with Mum and working on making her better to making her comfortable as she moved towards the end of life was profound. Palliative care was a beautiful, gentle, nurturing place, where Mum stopped having to parent us five children and we could stop parenting her. We knew she was dying; she knew she was dying. She was sharp and lucid, and we had two weeks to make peace with her life, our lives and what lay in between.

It’s a parent’s job to become redundant.

She talked about feeling very cared for in those last few weeks, more cared for than she had ever felt in her life. ‘Like a five-star hotel!’ she said. Not that she’d ever experienced such luxury. On the first night of Mum and Dad’s honeymoon, they landed in Sydney. Dad hadn’t booked a hotel and there were no vacancies. They spent the night at the Salvation Army ‘People’s Palace’. A shelter for the homeless. She was twenty-one.

‘Being so cared for,’ she said just days before she died, ‘has made me realise I never cared for myself.’

Family and close friends came and sat with her. Sometimes there were chats, laughs and reminiscing. Other times she slept as people sat by her bed. She spent as much time as she could with the older grandchildren. It was deeply moving for both Mum and the grandchildren to have that time together. Knowing she was about to die and watching her deteriorate physically as each day passed was a gift. So often, old people die suddenly or dementia reduces the ability to connect. We held the space for her.

On one of the last days that I headed to the hospital, my youngest son, Charlie, gave me a message to give to Mum. ‘Tell her I hope death is like waking up on a Saturday and realising you don’t have to go to school.’

In those last two weeks, she and I softened towards each other. My sister Helen remarked on the kindness between us, which she had not witnessed for years. Mum and I put our weapons down. Our disappointments, our anger, our resentment. I wondered how we could suddenly do it now that she was dying. All I know is we couldn’t have done it any earlier. She was who she was, I was who I was and we were who we were.

Suddenly, and gloriously, it was as if the aperture had dilated to let in more light. Instead of focusing on the foreground, I found myself pulling back to see the wider frame. The bad bits, the tough bits, were now blurred and faded, and the lovely moments were becoming brighter and more visible. Drawing my eye with their sweetness. Their beauty.

The contrast made it easier to see things I couldn’t see when I was still ‘doing’ the relationship with Mum. Enduring the tug of war, the cognitive dissonance, the battle between the vigilance to protect and the desire to connect.

When it was almost over, it felt as if I was at that point just before the end of a long journey, when – after weeks of sights and sounds, planes and trains, food, fantastic and fuck-ups – you’re totally over it. When you shift from travel to preparing to return and just want to be home. That day or so of longing to be in familiar surroundings, easy routine and your own bed. Then suddenly at the eleventh hour you get that last surge and find yourself thinking, ‘I’m not over this, I still have more in my tank, I’m not ready for this to end.’

When my friend Sarah heard Mum was dying, she messaged me: ‘It’s important to say, “I love you, thank you, I forgive you, please forgive me.”’ A friend who worked with the dying had passed this treasure on as Sarah’s own mother had died months before. Although I am fairly good with words and am ‘a ball of feelings’, as one of my best friends describes me, this collection of words was invaluable in its simplicity and clarity.

I’d been grieving my mother my whole life; knowing she was dying, I felt a huge burden lifted. With her death, the grieving ended. She did her best with the hand she was dealt. We were grateful. She had taught us many things. We’d take it from here. We told her this. She heard. She said she was ready to go.

One night, I had a strong urge to sit with her as she lay jacked up on morphine to kill the pain, Maxalon to prevent nausea and quetiapine, an anti-psychotic I’d asked the doctors to administer as she’d occasionally suffer what appeared to be terrifying moments of delirium. I drove through the quiet streets, parked in the underground car park, took the series of lifts and walked between buildings to the palliative care ward. I explained to a kind nurse that I knew it was after visiting hours, but I just wanted to sit with my mum. She gave me a smile and a nod.

The light was dim and soft. She looked peaceful under a pale green and orange mohair throw – ‘Aunty Pat’s blanket’. Aunty Pat was my father’s sister and one of the happiest, kindest and most generous people I have ever known. Mum and Aunty Pat were very close, perhaps each other’s best friends. Aunty Pat’s blanket kept her company for those last two weeks. One of the last things Pop, Mum’s father, said to me was, ‘The worst thing about getting old is watching all your friends die.’

I sat next to her, as she slept, watching the blanket rise and fall. She stirred, eyes closed, and I said, ‘Hi, Mum, it’s Catherine. I thought I’d read to you if you like. I’ve brought Tender Is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald.’

‘Oh, that’s a wonderful book. Don’t read to me though. Just read quietly to yourself . . .’

So I did. An hour or so later, she started babbling: ‘They’ve been trying to get me to move my bowels all day. They’ve given me four enemas . . .’ Then she stopped suddenly and it took a long time for the blanket to rise again. I thought, ‘Fuck. She’s dead and her last words were “They’ve given me four enemas.”’

During that week I mentioned something about the funeral to my sister Helen. ‘Funeral? There’s no funeral. Mum wants no service, no religion, no speeches and she’s leaving her body to science.’ I was shocked. Amazed. Full of admiration and joy. This woman, raised to be a handmaiden to the Catholic Church – no contraception, virgin at the altar, lugged herself and us to mass for decades – was dying an atheist? Holy fuck. Wasn’t death the time to cash in on the sunk costs of a lifetime of religion?

I’m not sure what Mum’s actual last words were, but Helen was with her during the last afternoon she was conscious. Mum drifted in and out, making sense for a bit, then none at all. From nowhere, she said, ‘Catherine’s using new words now’ – as clear as a bell.

What did that mean? ‘Catherine’s using new words now’? We’ll never know. Was it a slip into or out of delirium? Was it that I was speaking to her with tenderness? Or did she mean the stories I began to weave for her in her last few days?

I kept thinking about lovely things I’d forgotten. Little moments that had been obscured by my flinty sadness, my white-hot anger, my bone-deep resentment and my heart-breaking disappointment. My arrogant judgement. My fury.

As she slowly drifted away over those days, I reminded her of things about her that I loved. Her perfect handwriting and how she’d write diagonally on birthday cards on the opposite side to the printed wishes. How, in an autograph book I had when I was ten, she wrote, ‘To my daughter Catherine with stars in her eyes’. How she talked about birth and pregnancy with wonder and pride. How those seemed to be the only times she had experienced true and incredible joy in her body and what it could do. What she could do. I would ask her to tell her five birth stories over and over again. I never tired of them.

When I was eight, I woke up in hospital after having my appendix out and found a card on the table next to me. Her beautiful handwriting spelled out the shape of my name: ‘Catherine’. I opened it and read the first line. ‘You are probably very sore . . .’ I can’t remember what else she said; perhaps that I’d been very brave, that she’d visit in the afternoon and to be good for the nurses.

When people die, you get their whole lives, their whole selves, back. I began to journey back into her life and ask questions about her happy times and old friends, so I could make sure I had it all straight and so we knew to contact those important people. The happiest time in her life had been teacher’s college, between school and marriage. A gang formed, a combination of friends she made while she was studying and people she knew through the Catholic youth groups, the Legion of Mary and the Irish National Foresters. This bunch of Micks hung out together every Saturday night. They’d go to a ball if there was one, and otherwise they’d play cards together at someone’s home. They always said the rosary together before they cut the deck.

I started asking about all these people – how she knew each one and where they fit in. And as I asked, she told me more stories. How Peter went off to work as a missionary in Papua New Guinea, how she wrote to him every week and how she now realises he was probably gay and died of AIDS. How when Pat Green sat on the end of her bed and told her he was going to propose to Margaret, she cried because she fancied him. How Liz Carroll was from Sydney and the two of them would sometimes go on holiday to Liz’s family home in Coogee Bay Road and how Liz taught her to do the drawback. How Dad played the piano, and they all sang, mostly hymns . . .

Eventually she stopped talking, stopped eating and stopped opening her eyes.

Mum was a husk. It felt as if she was a carapace it was time to shed. We sat and we waited. We ducked home for naps, food, a change of clothes, a cuddle, a cry and some distance. We kept our darlings, our loved ones, our beautiful friends up to date. One of my favourite recharging moments was sitting on the bitumen in a car park space at the Yallambie McDonald’s late one night with Helen and her gorgeous mate Lisa, eating burgers, slurping on Cokes, talking, laughing, debriefing and smoking cigarettes.

That last week was like a long-haul flight. Uncomfortable sleep, crappy food, time suspended, no way to hurry it up, no alternative other than to be in the moment. Then the next moment. They were all the same. Blanket slowly up and down again. We were waiting for the moment when the blanket stopped. The big finale was nothing. Those rattling shopping bags of pills she took for years had served their purpose. They couldn’t make her better anymore. Better was now only dead.

Unlike during plane trips, there were no maps on the screen telling us how long until we’d reach our destination. And no ads spruiking the delights of embarkation – restaurants, shopping, glorious beaches, amazing jungles, spectacular views and pristine air. Delights that seemed unfathomable in the stale funk of a metal flying tube, in the dark, surrounded by strangers going through the same thing.

* * *

As you watch someone die, time continues to pass and you just do the next thing you need; food, drink, sleep, loo, distraction, speculate on how much longer the blanket will rise and fall. Repeat.

The last night Mum was alive, my sister and I stayed with her. It was supposed to be just me. Helen said, ‘I’ll stay too. It’s so relaxing just the two of us.’ I felt the same. We had a happy night. It felt light. We talked, laughed, took the piss, fussed over Mum, and reminded her of things she found funny or that had made her laugh. Mum always loved hearing us kids and our craic. For days, her breathing had become progressively slower and more laboured. Her ‘death rattle’, the sound a person makes when they are no longer able to cough effectively enough to clear their saliva, got louder and louder. The longer the gaps between her breaths, the noisier her death rattle became.

As the night wore on, Helen and I took turns sleeping on the camp bed. I played Mum classical music I knew she liked: Mozart’s ‘Requiem’, Vaughan Williams’ ‘The Lark Ascending’, Arvo Pärt. She was a huge classical music fan: her radio was rusted on to ABC Classic 24/7.

When the music wasn’t playing, I’d hear my sister, my beautiful baby sister, snoring gently, my mother dying slowly and the two clocks on the wall ticking in unison. The nurses and doctors who wafted in regularly felt like angels. I will never forget their compassion and kindness. Mum had a shit life but a five-star death.

Mum died the following day around lunchtime, and it couldn’t have been gentler. My two sisters and I were with her as she took her last breath in a riot of sunlight. She’d always called us, ‘You three girls.’ Her breathing changed from laboured to light. The three of us stood from our chairs and moved close to the bed. We knew this was it. We said, ‘We’re here, slip off whenever you’re ready’, ‘Go gently’, ‘May the road rise up to meet you’ and ‘Bye, Mum, thank you . . .’

Watching Mum die was the most beautiful experience of my life. I immediately felt light, relieved, liberated. I ended strong and with kindness. So did she. I felt as if I had circumnavigated the emotional globe.

People kept saying ‘Sorry for your loss’, but it felt then, as it does now, like a gain. When I told people Mum had died, they usually said, ‘It will hit you eventually.’ But it already had. It hit me as love and softness and deep quiet and peace. As freedom and empowerment. People think there is only one way to grieve. There are as many ways to grieve as there are to show love, be loved and feel love.

* * *

I’ve never been a fan of immortality. Stories and people need an ending. Mum’s death convinced me even more of that. Humans learn so much through death that we can’t learn any other way. It makes us better versions of ourselves.

And who knows what Mum learnt in those last few days of deep sleep. Just because she couldn’t verbalise or share what she was experiencing doesn’t mean she wasn’t learning amazing and important lessons. Sharing those lessons is not what makes them valid. Lessons learnt on the way to death may be the most profound, empowering and liberating a human can experience. Mum may have shuffled off this mortal coil with an overwhelming feeling of peace, care, insight, connection and power that would be impossible to achieve while alive.

Mum gave me everything she was able. People’s everythings look different. But they are their everything all the same. We’re all doing the best we can.

***

In addition to serving as an aesthetic principle, Kintsugi has long represented prevalent philosophical ideas. Namely, the practice is related to the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which calls for seeing beauty in the flawed or imperfect. The repair method was also born from the Japanese feeling of mottainai, which expresses regret when something is wasted, as well as mushin, the acceptance of change.

Kelly Richman-Abou – Kintsugi: The Centuries-Old Art of Repairing Broken Pottery with Gold.