Another brilliant piece from a GUNNAS WRITING MASTERCLASS writer.

I went to lunch with my grandmother and two of her friends at the local RSL recently. We went to play the pokies and enjoy the $9.95 seniors menu. This is not an uncommon occurrence but for some reason the conversation on this day stayed with me long afterwards. We often think of old ladies in fairly simplistic terms. They stereotypically like their knitting, a cup of tea (lots of milk) and bake a great scone/tea cake/chocolate chip cookie. Perhaps on this occasion I actually listened to them or perhaps they were more candid then usual, but I came away with the acute realisation that they exist in a world that is completely alien to mine. These women have experienced so much. In between stories of incontinent late husbands, haemorrhoids and hernias they throw in casual references to recently dead friends or those still languishing in nursing homes. I discovered that between them they have nursed four dying husbands, two sisters, a brother and helped to nurse countless friends. Despite this all three had a wicked sense of humour. They joked about blow jobs (“oh I couldn’t, I’d ek, I’d ek”), how difficult it is to wipe up after a trip to the toilet when you have haemorrhoids and how they were trying out online dating (“I’m looking for a friend WITHOUT benefits”).

I was fascinated. How, having witnessed and suffered so much misery were they able to continue to face life, and their not so distant death with such humour and courage? The familiar Nana that I had grown up with started to take on new dimensions. Somehow I had never considered this before. Elderly women are invisible in Australian culture. I have never read a book by or about a woman of this age. I have never seen a movie or watched a TV show that has an elderly lady as the leading character. I have so few reference points. Then another thought struck me, with startling clarity – if I live long enough this is going to happen to me too. Statistically speaking women live longer than men and more often than not it is women who take time off work to care for elderly relatives.

How does it feel it be nearly 80? To not just outlive, but nurse one or even two dying husbands on your own. To lose a son, a best friend, a brother or sister and support your friends through their own losses. To have collections of equipment in your home for when the next person you love needs to be nursed. Bed poles, commodes, walking frames and boxes of medications to lower your blood pressure, raise your iron levels, lower your cholesterol, soften or harden your stools as the need arises. To visit friends and relatives in nursing homes and know that you too are getting older. To watch them waste away, looked after by staff who don’t seem to care in an organisation that seems to be more of a business than a care facility. To know that you are closer to death than birth and to know intimately what it means to die. To have lived with a partner for fifty years and lose him. To watch him slowly fade away as dementia steals all the particular special things that made him who he is, that you loved. To have had a busy loving family who needed you for such a long time and wake up one day to find yourself alone in your house. No one to care for and no one to care for you. To go to family dinners and events and feel like you and your opinions and experiences are no longer relevant. You are from a different era. To have your family start treating you like a child.

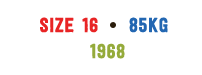

There are women like this everywhere. Mothers, sisters, wives, grandmothers. They have spent their lives doing all the unglamorous unpaid caring work that goes unnoticed. Raising a family, caring for relatives. They get up every morning, pull on their comfortable slacks, sensible non-slip shoes, white singlet and a blouse they got half price at Harris Scarf. They vacuum the floor that only three people have walked on this week and wash the two dishes from their dinner last night. They start giving away and donating the things they don’t need any more. “Can’t take anything with you where I’m going.” my Nana often says.

These women find the time and caring and the fucks to give about the countless, trivial problems of their children and grandchildren and then quietly go and have a mammogram, a mole scan, a blood test. Simultaneously preparing for death and doing their best to delay it. They unanimously agree over lunch that they want to go quickly. A nice stroke or a heart attack. They lament that voluntary euthanasia isn’t an option and then in the same breath tell me about how one of them took their terminally ill husband to a sex shop for the first time while he was still in a wheelchair. With the three of them cackling, the kettle is put on again as some more chocolate slice is retrieved from the fridge.

These women know how life starts and they know how it ends. They can reconcile the inevitability of death and illness whilst finding the motivation to get up every morning and face their lives with hope and love. I want to know how they think. I want to know what they think is important in life and what isn’t. What they would change and what they wouldn’t give up for the world.

I resolve to come back and start recording their stories.