Another brilliant piece from a GUNNAS WRITING MASTERCLASS writer

It was only when my children started to move out of home that I realised the enormity of my father’s journey. He came to Australia when he was 17 years old, and when he left, I wonder if his mother knew that she would never see him again.

It was only when my children started to move out of home that I realised the enormity of my father’s journey. He came to Australia when he was 17 years old, and when he left, I wonder if his mother knew that she would never see him again.

He came from Sicily, a harsh and unforgiving place – rocky, citrus bright, volcanic. He came from a brutal and unloving place, and by his word, a brutal and unloving family.

He came to avoid military service, which he had to do in the year he turned 18. This is why he had two birthdays – his true secret birthday of 31st December, born at home in silence. And his legally declared birthday of 3rd January, which pushed him into the following year for military service. But he had left by then.

The world was a big place in those days, journeys by boat took time, unlike the warp-speed air travel of today. Now, when you get on a plane, you arrive in a different country some hours later. Different language, different smells, but it is magical, like entering an elevator, where you walk in on the ground floor, and come out on the next level, in a different country.

The world was a bigger place in those days, without Skype or email, or cheap phone plans. Every Christmas we would ring, but the conversation would be stilted, and awkward. “Come sta?” Bene, bene, non ce male.” Each year, my nonna would be disappointed that I couldn’t understand her. The conversation between her and my father would fizzle out after a few minutes, but even that short call would cost more than my father earnt in a week.

My grandparents were illiterate, which is why my father and his brother have different surnames. The clerk in the Registry Office wrote the names down as they were said to him – Remato, Rimato, Renato. When my mother looked into the family tree, she found my grandfather’s military record from the first world war –his papers were in the name of Grimaldi.

I am named after my grandmother – Catina. But then again, when my mother went back through the family history she discovered her name was Agatina, but no-one had remembered.

I want to go to Sicily. I want to take my children there and say, this is your rock, this is your blood, this is your grandfather. The older children knew him, but the younger ones, not at all. He died when my daughter was 3 months old, by his own choice.

In the months before he died, he wrote his story. But he wrote it in Italian, or to be precise in the harsh and guttural Sicilian dialect. I have tried to read it, but one phrase stopped me from going further. He spoke of returning to Melbourne after a season of cutting cane in Far North Queensland. He spoke of returning to “mia piccola famiglia” – my little family, and it was a tenderness that I had never seen. Who was this man? I couldn’t read anymore.

I want to go to Sicily. I want to feel the harsh heat, the cutting rocks, the sting of salt, the olives and the lemons. My grandfather the fisherman also worked in the lemon factory. Years later, on the other side of world, we could buy bottles of lemon juice from this factory, in yellow plastic lemon shaped bottles. I bought these bottles of lemon juice from Cardamone’s where it smelt right – prosciutto, parmesan, espresso, pesce stocce. They called me “signora” when they served me.

My Nonna was an unhappy woman. My father told me that her first child died shortly after birth. How did women grieve in those days, at the end of the second world war in Sicily? There was no food, the family running from the bombed out seaside town, to the mountain village of my grandfather’s parents. My Zia Mela carrying her toddler brother on her back – she was only four or five herself.

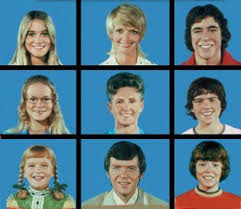

My father said that she didn’t know how to love, and that is why he never learnt how, not until he was an old man. Was there ever any joy in her life? I see photos of her, and I think I look a lot like her – the same build, the same strong features. But the lines on her face are etched more deeply.