Another brilliant piece from a GUNNAS WRITING MASTERCLASS writer

There have been very few moments of clarity during the three years in which I have had PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). Mostly, revelations made on my own or with my therapist will arrive only to be immediately marred by pasts and futures, failures and triumphs, pain and hope, thoughts and feelings. But there has been one revelation that has stayed remarkably and unwaveringly clear: I am terrified of getting better.

There have been very few moments of clarity during the three years in which I have had PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). Mostly, revelations made on my own or with my therapist will arrive only to be immediately marred by pasts and futures, failures and triumphs, pain and hope, thoughts and feelings. But there has been one revelation that has stayed remarkably and unwaveringly clear: I am terrified of getting better.

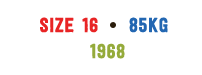

I have spent ten years – over half my life – either being traumatised or recovering from it. Most of my formative moments have been dampened by the strange, tarry soup that is my mind, which too often shares breath with some aspect of PTSD.

My faltering brain makes itself known in many ways. First, you have your daily run-of-the-mill PTSD stuff: nightmares, flashbacks, panic attacks, hyper vigilance, lack of concentration, irrational fears, etc. Then you have the funny-in-hindsight incarnations: everything suddenly going blurry because your brain has decided that the best thing to do is to start shutting down; crying hysterically in a supermarket because you can’t find the lentils; failing to recognise your own hands; forgetting how to turn taps on; battling sudden urges to drive your car into a tree so that everything will be dark and quiet for a minute.

Small things are celebrated as though you just won the Nobel Prize: you manage to have a shower without lying down in the bottom of it; you walk two hundred metres alone down the street without thinking everyone will kill you; you don’t have to clip your fingernails painfully short because you’re pretty sure that this week you won’t scratch yourself until you bleed.

Part of me loves this abnormality. Some days I ache for something to go wrong, because those moments prove to me that I am not okay. It validates me. It makes my past mean something important. Every flashback, every nightmare is proof that I have lived through something horrible. I have suffered and I am in pain. The scratches I give myself are not for other people to see; they are for me. Each brown scar left on my skin reminds me that this is real. “You are suffering,” they seem to whisper. “And it’s okay that you are. You can prove it to anyone who doubts you.”

And so, I stand between two cliffs, balancing on a huge beam: sore, exhausted, bored, terrified, immensely proud of myself for getting this far without falling off. I look down and see the ravine into which I almost plummeted. It is filled with a strange fog, grey and dense and unforgiving. I don’t want to fall in. I can’t fall in; I’ve come so far. I look behind me. Horrific beasts stare greedily at me, the stuff of children’s books – all sharp teeth and multiple eyes – wishing me to fall, lulling me back to them, hoping I’ll die. I don’t want to turn around. I can’t; I’ve come so far.

And so, it would seem, the only thing left to do is to walk towards the other side. But still I falter. Who will I be when I get there? Will I still be me with solid ground beneath me instead of fog, with the creatures behind me, out of sight? Who will be there, waiting for me when I arrive? What will happen to me without the daily reminders of the pain that has permanently shaped who I am? It feels like forgetting your mother’s scent, like forgetting the name of your childhood toy.

PTSD is strangely safe: I know it well. I know how it works and what to do and who I am in its orbit. I have a set of rules, a set of consequences, a set of excuses that lets me say “no” to risk and “yes” to comfort zones. I have become so good at managing it that it feels like I could live like this forever. It means that I am extraordinary: look at me, look at what I can do in spite of my suffering, in spite of my pain. I don’t have to achieve anything great just yet. Getting through each day without dying is triumph enough.

I am terrified that when I am well, when I am healthy, when things are fixed, I won’t be extraordinary, I’ll just be normal. I’m terrified of giving up the fight for a messy, vivid, wonderful life; of settling, of slithering mindlessly into health and the everyday, of getting to the other side only to find out that I am not a remarkable young woman who deals with adversity, but an unremarkable nobody who blends into the crowd.

But I can’t stay here teetering in the middle of the beam for much longer. I am getting too tired, too frustrated, too bored to stand here anymore. I have to make a choice. If I don’t start moving I will fall.

And so, I take a step towards the other side.