Another brilliant piece from a GUNNAS WRITING MASTERCLASS WRITER

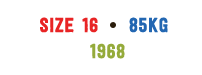

It was the first time in twelve years I’d ever seen him cry. Even after his mother died he’d remained dry eyed, only becoming quieter than usual (and he was already mostly silent on a good day anyway), but still presentable to the general public as the stoic, capable man. In those first days after our baby was born silent and still, as my body folded in on itself, as I lived life from what felt like the bottom of a well looking up to a pin prick of light, it was his tears I remember most vividly. The odd way his face twisted, it was like that of a stranger. As he sat in the chair beside the hospital bed and wept, I lay in shock. His tears disturbed me in the way that a toddler is disturbed to see his parent cry, seeing the shifting of the way that things should be, a change in the natural order of things. Only in those two days after she died, after her little warm body came to us but never moved, did he cry. After two days that window into him closed up and I never saw it open again. So I alone was left to publicly carry our grief, to show to the world the pain we felt, to answer the well meaning but awkward questions at BBQs and school pick ups about how we were coping, and did we want the frozen lasagne Carly Wood from next door had for us? He withdrew, went on autopilot while I felt raw and exposed to the world. My post partum body without the baby, my engorged breasts and sagging stomach – was a physical reminder of what we didn’t have. But he was determined to carry on, back to regular life.

So this heavy darkness became mine to endure alone. He continued to work, go to his job five days a week, bath Josh and Luke when he got home, mow the lawn, wash the car. He invited friends around every weekend and poured them large glasses of cheap wine and talked about his theories on things – ethics in sport, public vs private education, Donald Trump. He skirted away from any question of how he was, refused any form of counselling, slept like a log beside my chronic insomnia. Despite his mask of normalcy, I knew that he was also shattered into a thousand tiny pieces. I knew because of those two days of tears, that moment when the guard was down. Because I knew this inescapable truth of his, I could never forgive him for the role he made me play in those months and years after she died, for he made me bear that cross alone.

‘Look Daddy’, Luke said to him one morning a few months after it happened, proudly showing off his costume for the end of year kinder concert that I’d spent half the night sewing and gluing together (I couldn’t sleep anyway, so why not scald my fingers with a hot glue gun?). ‘Look daddy’, he persisted when he received no response, face beaming with hope, his still slightly rotund belly for a four year old straining against the sequined sash around it. ‘Yes mate, you look great’ he said. But his eyes, which before would’ve lit up at Luke’s proud little stance, stayed blank. For what I saw was this – he was no longer there.

To me at least there was still magic in our little family, in our two children who were still in those preschool years where their parents were their world. Others constantly reminded me that I was ‘lucky’ I already had children, that it must make it ‘easier’. They didn’t understand that nothing makes all those small little horrors you experience every day after loosing a child – of taking apart a cot never slept in, of meeting a the friend in the street who wonders where the baby is – easier. But still, I saw magic in Luke and Josh’s small hands slipping into ours when we walked to the park and their sleeping faces that I snuck in and kissed when they were tucked up in bed at night. And in my intense grief, I could still see it. But I knew he couldn’t. He had became a ghost in our house.